This article originally appeared in the Sports Issue of Exploring Magazine.

by

David Barker

It has been said ironically that England and America are two countries separated

by a common language--English. It could just as easily be said that Japan

and the United States are similarly separated by a common sport--baseball.

Robert Whiting, in his book You Gotta Have Wa, believes that sport

can be a means to understanding subtle aspects of culture and national identity.

And when two countries share a common sport, the differences are often more

telling than the similarities.

Baseball was introduced to Japan at the start of the Meiji Period (1867-1912)

by Horace Wilson, a young American history and English teacher. As Japan struggled

to emerge from three centuries of feudal isolationism, Wilson taught his students

at Tokyo's Kaisei Gakko the rudiments of his country's national pastime.

The sport quickly caught the spirit of the Japanese people: by 1905, college

baseball was Japan's number one sport. Professional teams were instituted

in 1935, and now every year twenty million fans faithfully troop out to the

ballpark and cheer on the Yakult Swallows, the Taiyo Whales, the Nippon Ham

Fighters, and the Hiroshima Carp, among others. Japan has been baseball crazy

for over a hundred years.

As one Japanese writer put it, "Baseball is perfect for us. If the Americans

hadn't invented it, we would have." On the surface, Japanese baseball

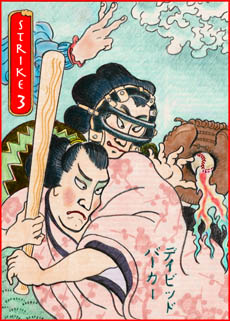

(besuboru, or yakyu--field ball) is similar to its American counterpart. Nine

innings, nine players a side, and it's suree sutoraikku (three strikes) and

yer out at the old ball game. But look closer (and Robert Whiting did) and

you'll see differences that reveal how the game has been adapted to Japanese

culture.

Before the introduction of baseball, group sport didn't exist in Japan. Athletic

competition consisted of individual feats and one-on-one contests such as

Sumo wrestling, kendo (fencing), horseback riding, and swimming, all extensions

of military training. Since there was no equivalent word for "sport"

in the Japanese language, a new word was coined: supotsu.

Baseball expanded the notion of competition to include a vital aspect of Japanese

society: the importance of the group. Historically a clan- or family-based

society, Japan has always demanded that the individual subordinate him- or

herself to the group in order to maintain group harmony, or wa. Any

individual activity that interrupts the smooth flow of wa is dealt with instantly

and harshly. As the Japanese saying goes, "The nail that sticks up will

be hammered down."

American baseball thrives on the nails that stick up. The game has always

been defined by its heroes--the Babe Ruths, Christy Mathewsons, Joe DiMaggios,

and Willie Mayses. It is set up for the larger-than-life confrontation between

pitcher and batter, and how the team fares is almost secondary to the accomplishments

of its heroes.

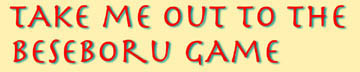

Japanese baseball enjoys this mano-a-mano aspect of the game as well, harkening

as it does to the essential nature of samurai combat. But stars like Sadaharu

Oh (Japan's great home-run hitter and the closest thing they have to a superstar)

are exceptions to the rule. Team attitude is paramount, and as a result the

game becomes, by Western standards, a little, well...boring.

Besuboru is played as if nobody wants to be the one to make a mistake.

In America, the home run is king. The ultimate is the dramatic blast that

knocks in three runs and wins the game. In contrast, Japanese games are won

by bunts and walks. Pitchers throw a lot of curve balls and nibble at the

corners of the plate. Three-ball, two-strike counts are common in Japan, and

consequently there are a lot of walks. Nobody wants to be the one who serves

up the homu ran. In the U.S. of A., this pitching approach is considered somewhat

effete, and the prevailing mentality is more one of "C'mon, throw me

your best fastball, let's see what you got...." In the States, the players

are more apt to challenge one another physically, and this is known affectionately

as "country hardball."

Japanese are attracted to baseball because of its relatively slow pace. On-field

meetings are convened to consider every possible factor in detail before a

decision is made. Like a Japanese business meeting, the game can go on, seemingly,

forever. According to Warren Cromartie, an American playing in Japan, "Managers

in Japan are afraid to make quick decisions, because they are afraid of making

a mistake. They have to discuss everything to death with their coaches before

they make a move. I played one half-inning in Osaka that took forty-five minutes.

That must be a world record."

The Japanese attitude toward practice also reflects a different cultural approach.

Japanese teams are allowed a maximum of two Westerners (gaijin, or "outsiders,"

not necessarily a derogatory label). Most American ballplayers are literally

in for a rude awakening when they begin practice, Japanese style. Beginning

at dawn and continuing till dark, workouts resemble a Marine Corps drill instructor's

most sadistic fantasy of Boot Camp Hell. Commonly referred to as death or

gattsu (guts) drills, these exercises in marathon running, fielding (a thousand

ground balls in succession), and batting allow the player to demonstrate effort

(doryoku) and fighting spirit.

These highly prized attributes are an extension of the samurai concept of

bushido, the way of the warrior. This work ethic is reflected in all aspects

of society: each and every sarariman (salaryman--worker) is expected to have

it. The Japanese don't play baseball, they work it.

American ballplayers consider this approach foolhardy. Practicing while tired

is thought to produce bad habits and increase the risk of injury. They go

out to the field, stretch, warm up for forty-five minutes, knock the ball

around for a while and then go out and have a few beers with the guys. To

them, baseball is not designed to test one's loyalty, self-control, moral

discipline, and selflessness. What Westerners call a pastime becomes, in the

hands of the Japanese, a rigorous spiritual form. Needless to say, most gaijin

ballplayers in Japan don't last long.

I recently attended a ballgame outside of Osaka. Initially, my attention was

drawn to the fans. In the more expensive box seats, people were seated quietly,

watched the goings-on in the field with the same detachment and reserve typical

of Japanese social demeanor. But in the cheap seats along the first- and third-base

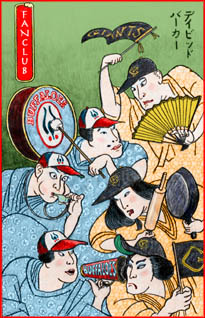

lines, a different atmosphere prevailed. Five or six oendan, or fan clubs,

were cheering on the hometown Kintetsu Buffaloes. Each group was trying to

outdo the others. Huge banners were being waved, and the aisles were clogged

with rows of bright happi-coated cheerleaders with samurai headbands and megaphones.

They were exhorting the fans to yell and chant together, and to drum their

plastic megaphones in a never-ending rhythm. The whole stadium pulsed with

energy.

In many Japanese stadiums, fans spur their team on with whistles, gongs, taiko

drums, even frying pans. The fervor and cumulative sound is not to be believed.

One New York television producer described a long afternoon spent in the middle

of a Yomiuri Giants' oendan: "These people are lunatics! There's more

noise here than the World Series and the Army-Navy game combined. How do they

keep it up?"

The fan clubs point out another function of baseball in Japanese society.

The average sarariman works hard, and is expected to hide his true feelings

and desires during the business day in deference to the company. And when

alone or in a small group, this attitude continues (as in the case of the

small, quiet groups of fans). But the oendan is a perfect escape valve for

the internalized emotions and pressures of daily life. There is nothing better

than to get together with other like-minded fanatics and sing, say, the Tokyo

Giants' fight song at the top of ones' collective lungs:

To the sky with fighting soul,

The ball soars and soars with burning flames.

Aah...Giants.

Ever proud of the name

Their courage lights up the field.

Giants...Giants...

Go...Go...Giants Troop.

Like literature, art, music, and theater, sport can reveal a lot about a nation's

cultural identity.

Jacques Barzun once said, "Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of

America had better learn baseball." And Suishu Tobitsa sums it up pretty

good, too: "Baseball is more than just a game. It has eternal value.

Through it one learns the beautiful and noble spirit of Japan."