| fact, it takes some doing to perceive the common ground among a water wave, a sound wave, a light wave and a wave of fashion. The best way to know more than a textbooky definition of a wave is to learn through experiences with and reflections on the commonalties among the various embodiments of a wave. It would be much the same with any concept, such as that of a family. Knowing only one family member tells nothing. One needs to know children and uncles and cousins and brothers and grandfathers and mothers, to understand the concept 'family'. Only then can the concept be extended to include the "family of man" or the chemical family of halogens. Natural history museums and anthropology museums seem to know more about the virtue of multiple examples than do science centers. Too often, these centers will show just one example of refraction, one of reflection, one of interference and one of diffraction and be satisfied that they've "covered" the behavior of light. There is an additional reason for providing a multiplicity of contexts. Each exhibit on one topic can belong to a different chain of exhibits on another topic. For example, some resonance exhibits also fit into the theme of musical instrument, some into the exponential section and some into the group of those on electrical inductance and capacity, etc. We | ||

Sand dances on bowed metal plates showing patterns of vibration | |||

| examples of resonance and standing waves. There are resonances in air columns, in strings and ropes, in metal plates and rubber membranes, in rods and springs, in water and in mechanical wave machines. We even attempted to illustrate resonances in solids with a remarkable jelly-like substance but unfortunately the only resonant frequencies that would produce an amplitude sufficiently large to be seen with a strobe light were too close to human brain rhythms for prudent display. We also have over a dozen exhibit pieces on binocular vision and size distance judgments, and almost as many on the role of edge effects and lateral inhibition in the eye. We even demonstrate Von Bekesy's model for lateral inhibition in the ear. We have eight different exhibits on gyroscopes and rotary momentum and forces, half a dozen or more pieces on composition oftwo perpendicular motions including a pendulum, a drawing board, oscilloscopes, and color television sets. We have a section of 15 exhibits on things which grow or decrease exponentially or logarithmically. There are at least two considerations that dictate having such multiplicities. Science has not only unearthed many intriguing (and useful) natural phenomena, it has also provided us with a conceptual framework for thinking about them. Our concept of wave is much more general than any particular kind of wave. In | |||

| |||

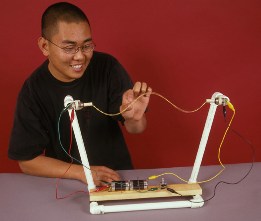

A string forms a wave with nodes and antinodes when twirled by motors. | |||