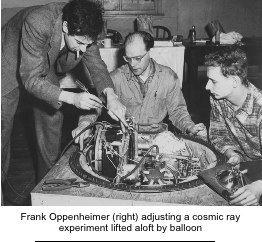

| It is, therefore, more important than ever that museums assume the responsibility for providing the opportunities for exploration that are lacking for both city and suburban dwellers. It would be fine indeed if they would, but it will take a bit of doing to do so properly. If museums are too unstructured, too unmanageable, people get lost and simply want to get back to home base. On the other hand, if they are too rigid, too structured or too channeled, then there are no possibilities for individual choice or discovery. Exploring, like doing basic research, is often fruitless. Nothing comes of it. But also like basic research, as distinct from applied or directed research, exploring enables one to divert attention from preconceived paths and to deviate from the original path to go after some intriguing lead: a fragrance or a sight or smell or an interesting street or a cave or even a hole in the ground or a sudden open meadow encountered in the woods or a patch of flowers that leads one off the trail. Often it is precisely as a result of initially aimless exploration that one does become intensely directed and intensely preoccupied. Painters often carry a sketchpad on their wanderings. Durer became absorbed in the sketching of hands, Chagall with horses, mules and donkeys pulling wagons. Albers became preoccupied with squares. I, as a physicist, became absorbed with the origin of cosmic rays in an accidental way. I was invited to go to the University of Minnesota in the late 40's because General Mills was learning how to make huge helium-filled balloons that would carry a large payload 20 miles up into the atmosphere. We thought they would provide an opportunity to study nuclear physics by studying the impact of the cosmic rays that are found at high altitudes since very large high-energy accelerators did not exist at that time. We developed an elaborate apparatus for this purpose, but at the last minute we also attached a stack of photographic plates to the balloon. When these came down, we discovered that these photographic plates showed, not just the expected tracks of hydrogen nuclei, but also very dark, wide |  | ||

| tracks of the nuclei of all elements. This discovery opened up a whole new field of study. Although that discovery was made in 1948, the people who were in our group at the University of Minnesota and the University of Rochester are still, 44 years later, tracking down the discovery that was made simply because we added those photographic plates to supplement the main instrument of the experiment. It was really an exploration that paid off in an unexpected way. It is those things that are found through one's own exploration that often tend to seem particularly one's own. This proprietary interest can exist even if it turns out that other people have made the same discovery. The things that people discover on their own in a museum usually lead them to bring back their friends, children or parents. It is those things that they remember most and tell about and go back to see over and over again even 50 years after finding them. Whenever we move exhibits to new locations in the Exploratorium, many visitors frantically ask us, "Where is this...what happened to...?" They had come back specifically to show somebody an exhibit that they had discovered during a previous visit. It is exploration that leads to the discovery of unexpected novelty, and it is invariably such unexpected novelty that really moves science and technology into | |||