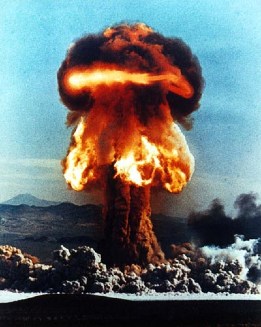

| Certainly this process is manifest as a sentimental fruit of science in the way we now react to the inanimate world. But unfortunately we are still filled with vague fears. It often seems to me that the total amount of human fear may be constant. For although we are not as filled with haunting fear of earthquakes, bacteria, or lightning, many people are increasingly scared of what people can do to each other, whether by using guns and clubs in the streets, or with nuclear bombs or carcinogenic food and environmental pollution. Too often our collective responses to the fears of what people can do to each other are irrational, mutually incompatible and confused. For the most part, people are barely able to distinguish which of all the possibilities for inflicting human terror are most threatening. | Whether they can do so is not yet clear. Certainly, social scientists have developed many new tools, social indicators that, so to speak, extend the range of our collective social acuity for observing patterns. Improved pattern recognition enhances our ability to foretell the future. But this ability is not very well developed even in the much simpler domain of the physical sciences. Unfortunately, many social scientists have concentrated on using their ability to predict the future as a test of their understanding and the reliability of their instruments. But they too rarely use observations and measurements primarily in order to get a better understanding of what is actually happening in people and in societies. There is one outstanding example of social invention that may have been the result of such deeper social understanding. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, French philosophers developed the notion that it is impossible to govern a populace without having at least the implicit consent of the governed. This insight led to the recognition that such underlying consent could and should be expressed as overt consent, and thereby led to the constitutional inventions that rely on popular suffrage. On the other hand, I find that the general use of the Stanford-Binet IQ test provides a counter- example to my admittedly somewhat speculative example of constitutional invention. Almost immediately after its development, the test was used to help judge how well students would do in college, etc. Certainly measurement is an important and usually essential step in the development of the sciences, but the ability to predict what is going to happen is a poor indication of the quality of the fundamental sciences. The IQ tests have not really illuminated the nature of intelligence any more than Galileo's invention of the thermometer in the sixteenth century gave insight as to the nature of temperature. This insight was not arrived at until late in the nineteenth century. And temperature is a much simpler concept than intelligence. | ||

| |||

| Perhaps social scientists can use what they discover about the behavior of people and societies to provide the raw material for inventing institutions that protect people from people and which, at the same time, provide social tools that enable people to satisfy their innate physical, mental, and emotional needs. | |||