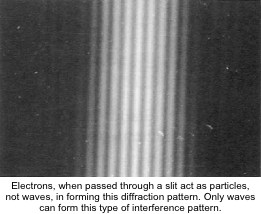

| of heresy. This is a change that has developed during the twentieth century and that has had a very profound influence on the way that we think about nature. The change has come about through the study of the tiny scale of atomic and subatomic matter, of the huge scale of cosmology, and of the incredibly complex interlocking interactions encountered in biology. These are domains of nature in which the details are completely removed from our ordinary experience. The problems first appeared in the study of electrons and of light. A great list of experiments showed conclusively that electrons behaved like the particles and light like the waves of everyday experience: like BB shot on the one hand and water waves on the other. But an equally valid long list of newly performed experiments that asked questions in different contexts showed electrons behaved as do familiar waves and that, in other experiments, light arrived in small bundles of energy as does a BB pellet. It makes no sense whatsoever to say that light is both a wave and a particle, that it spreads out in all directions like a wave and also travels in one direction and lands in a certain spot with a splash! In some contexts, beams of electrons behave like waves and are waves; while in other well-defined experimental contexts, electrons behave like and are particles. Neither statement or view is a heresy. There is a mathematics of electrons that can describe their behavior in these different contexts, but there is no way of making sense | of this duality of description that can be based on ordinary human experience. With people, there also appear dual descriptions that are contradictory and can only be valid descriptions when applied in very different contexts. There is no mathematics with which to bridge the gap between these dual descriptions, but our experience with electrons and light indicates that there must be bridges beyond our experience. For example, neither the statement 'there is no purpose that is fulfilled by people' nor the statement 'everything people decide to do is for a purpose' need be considered a heresy. From a cosmological point of view, there would not be any difference if there were no people in the universe. On the other hand, it is impossible to talk about human beings or to properly describe them or ourselves without using the idea of 'purpose.' We are always (or almost always) doing things for a reason, even building Exploratoriums. There are many other value dualities that apply to people, and to me it has made a profound difference in my thinking to know that such dualities are required even in describing inanimate nature. I can be reassured that thoroughly contradictory ethical statements need not, either one of them, be a heresy when applied in the appropriate contexts. This possibility does not imply that there are no ethics or distinctions of right from wrong, but it does imply that we can mollify some of the fiercest intellectual battles of the present and the past. We need to recognize the need for contradictory but equally valid descriptions of matters that are not and never have been part of human experience. By accepting this need of dual and incompatible descriptions, we have greatly simplified our view of ourselves as being embedded in a concordant view of nature. For this relief we can, in large part, thank Niels Bohr and those who worked along with him. In conceiving the Exploratorium we have had these sentimental fruits of science in mind, but we do not present them as such. However, we have been doing things for a purpose. If nothing else, we have created a delightful | ||

| |||