art which in many ways deteriorated as the painters became more skillful. I realized from observing the progressions in Italian art the kind of things that happen in an art or a craft as people use their increased skill to elaborate and embellish. Years later I realized that a similar entrapment by technique and technology also happens to physicists (as well as to three star generals). Jackie, my wife, and I engaged in a similar form of systematic learning when we lived, for a year, a couple of blocks away from the British Museum in London. We studied the Chinese porcelains there. We learned the names and epochs of the dynasties, and were able, by the end of our stay, to test ourselves on the recognition of the various patterns and textures in the Chinese plates and bowls, an ability that we enjoyed but never had a chance to use. It was during that same year that I visited the science and technology museum in South Kensington. It reminded me of the fine beginnings and the subsequent demise of a science museum in New York City that occurred while I was in high school. I realized what a scandal it was that there were so few and so few good ones in the United States. This realization managed to really alter the rest of my life and therefore represented still another kind of learning that can happen because of museums. After repeatedly visiting and studying the South Kensington Museum, I traveled to look at other science museums. In Munich I saw one lone machinist who had come upstairs to use a very fine large milling machine that was supposedly only on display. He had plugged it in just for his own purposes of making an exhibit part. That museum experience led me to the realization that machines and carpentry shops usually provide the most genuine technology that occurs in a science museum, a thought which then led to having our Exploratorium machine shop in full public view. At the Palais de la Decouverte in Paris, I watched young demonstrators and realized that they were using teaching as a part of their learning since many of the demonstrators were college students, a realization which later led to |  | ||||

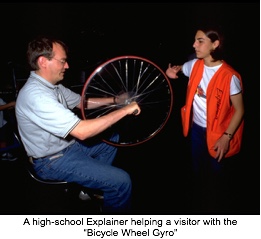

instituting an Explainers Program for high school students at the Exploratorium. A visit to the California Academy of Sciences made me aware that a charm of an aquarium was due to the fact that the fish, although not touchable, are always in motion. Therefore, as much as is practical in a science museum, one should have moving devices that the visitors can stop and then control manually to see how they work rather than static demonstrations that the visitor activates. There is today, especially among some science museum people, a tendency to discount some of the traditional museum techniques. In fact, I myself have argued that the techniques of television and film for portraying, for example, the African Veldt or of Cousteau in the sea, had made obsolete the traditional dioramas. But I recently visited the Denver Natural History Museum and found their dioramas so very, very wonderful. I felt as though I were up in the high country or wandering through fall aspen trees. But even more important, each diorama was full of things to discover: a lizard, a bird's nest, a clump of columbine. I and my companion could spend ten or fifteen minutes finding such things and pointing them out to each other, a kind of activity that is utterly impossible with television. I mention these kind of learnings to emphasize that museums can be used in such a great | |||||