| |||

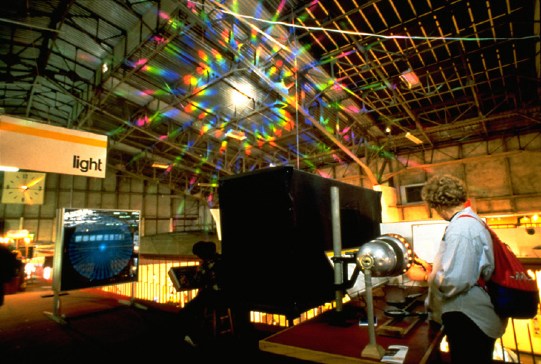

Light spectra splash on the roof of the Exploratorium as sunlight passes through a diffraction grating. | |||

| we invented the giant 400 lb. Resonant Pendulum exhibit. When we asked how can we best show that matter absorbs and re-emits light, we subsequently decided to develop a group of exhibits on phosphorescence and fluorescence. A very large number of our exhibits arise in this way. We first try to decide what kind of effects or ideas are fundamental to an understanding of some aspect of science or nature. Then we sort out which effects are easier to understand if they are demonstrated rather than read about. Finally, we grope around for ways to effectively and captivatingly illustrate such effects. Outsiders who learn about what we are searching for will frequently help. Phil Morrison called from MIT to tell us of the exponential behavior of a Bouncing Ball, Luis Alvarez sent us an article on a sequential array long focal length lenses. Occasionally a staff member will read about some work in a journal or newspaper and contact the author. We gather a group of experts in linguistics, for | example, or in visual perception. Invariably the group provides us with a great raft of ideas to work on. Since, as an ongoing process, we are expanding exhibit curricula and filling gaps in the ones we have, we have been able to afford the luxury of being responsive (albeit also selective) to the continual flow of ideas and of actual exhibit pieces that visiting scientists, teachers and artists bring to us. I have used the exhibits in the Exploratorium as illustrations because I know them so well. But this paper is not about the Exploratorium. It is about some of the very many considerations that govern the way in which exhibits can be conceived and designed in any science museum. My discussion has not touched questions of safety, or maintenance, of handicapped person accessibility, of fabrication techniques or of the all-important graphic | ||