| Exhibit Conception And Design | |||

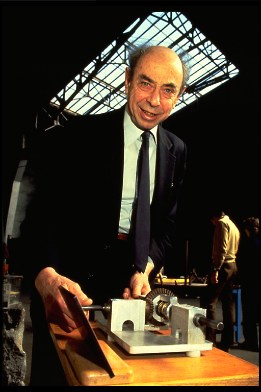

| Frank Oppenheimer, Exploratorium Presented in Monterey, Mexico 1980. Meeting of International Commission on Science Museums | |||

| In talking about exhibit design, I want to avoid a propensity that frequently plagues discussions about teaching, namely: telling people how to teach without any reference to what they are teaching. The way in which one designs exhibits depends crucially on their broad subject matter as well as the detailed content of each exhibit. I will therefore stick to some aspects of what we have learned at the Exploratorium. There we have exhibits on sensory perception, light and optics, sound, resonance and wave motion, electricity, rotation and angular momentum, exponentials, patterns of motion and rhythm, on the nature of heat and temperature, the behavior of gasses and liquids, nerve encoding, marine animal behavior, simple engines and a modest collection of miscellany that exists because it intrigues one or another member of the staff. This list, and it is not even all inclusive, must sound pretty diverse, but in our minds there is a thread that connects each topic with our starting point: human perception. The Exploratorium is about nature and one of the major accomplishments of science has been to demonstrate that there is a unity to the diversity of nature. There are relatively few fundamental forces, stars are suns, planets and moons fall like apples, electricity produces magnetism and magnetism produces electricity and they both combine to create light. It is hoped that the visitors to the Exploratorium sense this connectedness. This objective may, in our case, be helped by the circumstance that all our exhibits are in one gigantic room. But even if the visitors miss or do not formulate this grandiose idea, it is vital that we ourselves keep it in our mind. A museum can resemble a musical composition, a symphony in which even though the |  | ||

| listeners may not be aware of the structure of the piece, they must sense that it exists because the composer was disciplined in his efforts to achieve the coherence of his composition. Museums, at their best, require their creators to be guided by a similar kind of discipline. At the very least one can hope that visitors rarely say to themselves, or to each other, "Why in the world do they have that thing here?" There are some general precepts that we adhere to: We endeavor, for example, to display multiple examples, in a variety of contexts, of interesting or important phenomena. We have about 18 different | |||